Vietnam is one of Asia’s most popular tourist destinations, and many of the tourists are intrigued by Vietnam’s fashion in addition to the scenic charm of this South East Asian country. This article will introduce you to Vietnam’s fashion, Vietnam’s garments and fashion accessories, some traditional, some modern with that unique Vietnamese flavour. Fashion in Vietnam is as exciting as the country itself! Vietnam, the land of black pepper, snake wine and home to the world’s largest cave that can send your mind spinning, has a fascinating fashion tradition. Let’s dive in, by starting off from the men’s fashion of Vietnam.

What do men wear in Vietnam?

Most Vietnamese men usually wear modern western attire, but there are men who love to show their love of their roots every now and then. Here’s the list of the most prominent Vietnamese traditional items and the modern items worn by men that have Vietnamese roots.

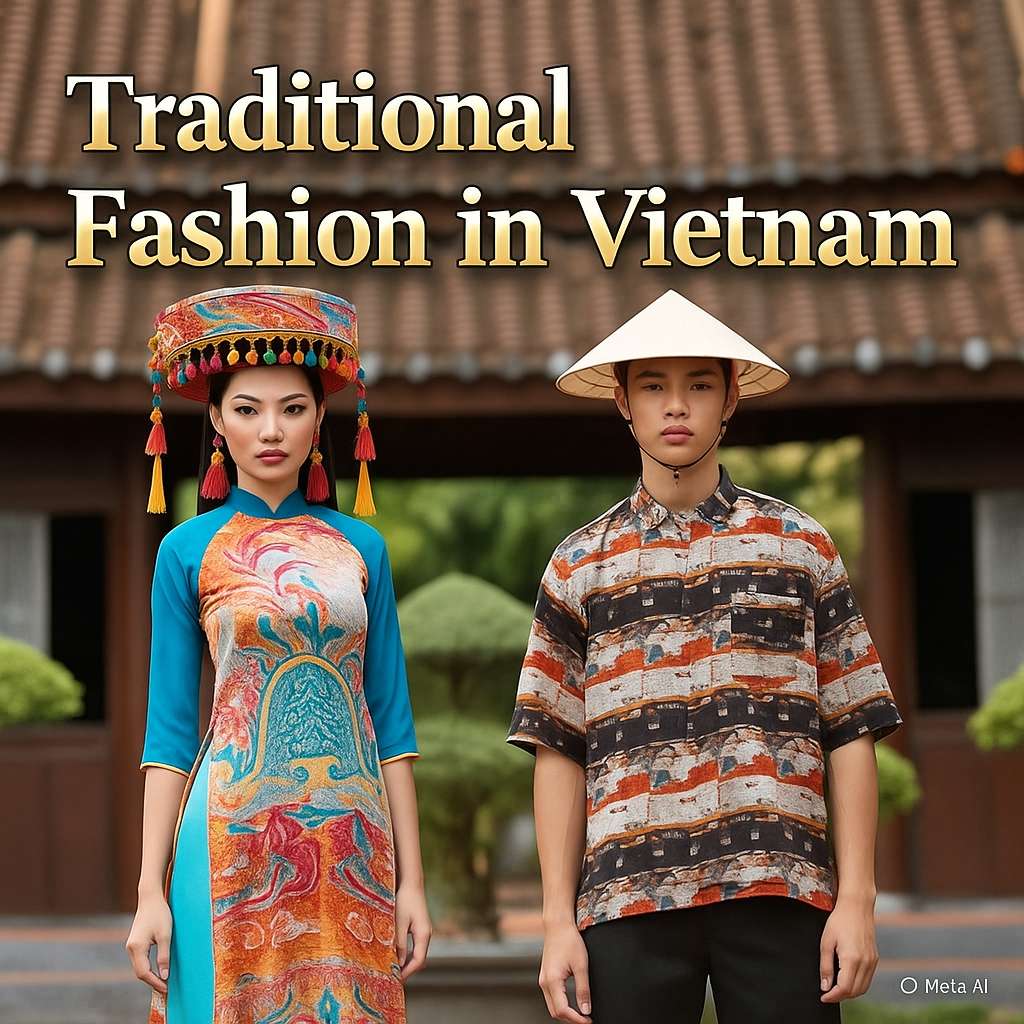

Men’s Áo Dài or Áo Dài Nam:

Áo Dài (pronounced ow yai) means “long shirt” in Vietnamese. This ankle-length tunic, with elegant side slits and a high collar, hugs the body and flows gracefully over loose silk trousers. Traditionally worn by grooms, scholars, and dignitaries, especially during weddings and Tet (Lunar New Year), it symbolizes pride and refinement. Often made of shimmering silk or synthetic blends, its form-fitting shape and stiff structure embody Vietnam’s elegant heritage—blending solemn tradition with contemporary poise.

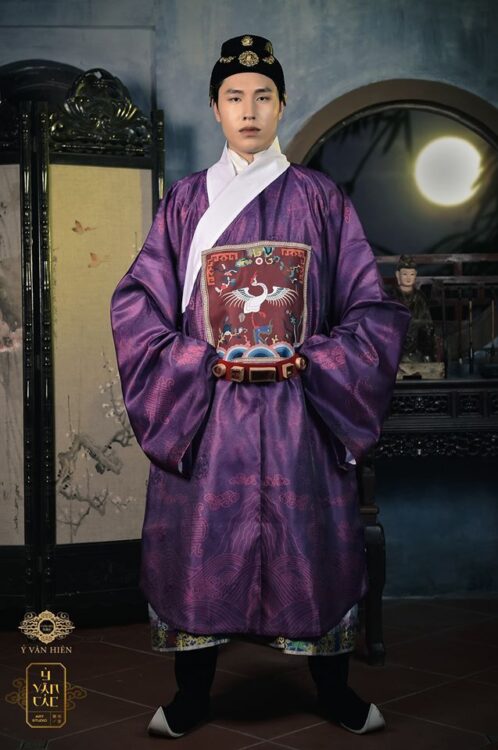

Áo Gấm Nam:

Áo Gấm Nam (pronounced ow gum nahm) means “brocade shirt for men.” A shorter, richly textured tunic, it’s made from thick silk or velvet woven with patterns of dragons, phoenixes, or clouds. With its stiff form and upright collar, it echoes royal formality. Not for daily wear, this garment shines during ceremonies, cultural festivals, or reenactments. The luxurious fabric and vivid colors demand attention—transforming any man into a noble figure of Vietnam’s dynastic past. image source

The resemblance of a vietnamese Áo Gấm Nam and Áo Dài Nam to Indian Kurta Pajama and Sherwani is uncanny. The traditional Indian fashion has a lot in common with other Asian cultural fashion traditions.

Áo Giao Lĩnh:

Áo Giao Lĩnh (pronounced ow zow ling) means “cross-collared shirt.” This ancient, robe-like tunic overlaps in the front and ties at the side. Its relaxed fit, wide sleeves, and breathable linen or silk construction reflect simplicity and scholarly elegance. Commonly worn in imperial times by Confucian scholars and monks, its asymmetrical front carries symbolic weight—left-over-right signifying harmony and humility. More than just clothing, it’s a statement of quiet intellect and cultural reverence.

Áo Bà Ba or Bà Ba Shirt:

Áo Bà Ba (pronounced ow baa baa) translates to “Ba’s shirt”—a Southern staple of comfort and utility. This collarless, button-down cotton shirt is breezy and practical, ideal for tropical climates. With a loose fit and no-frill design, it’s worn with matching pants for farming, fishing, or market visits. Its simple structure ensures freedom of movement, making it the daily uniform of rural life in the Mekong Delta. Unassuming yet iconic, it’s a garment built for hard work and easy living.

Quần Bà Ba (Bà Ba Pants):

Quần Bà Ba (pronounced kwun baa baa) means “Ba’s pants.” These mid-calf, drawstring trousers are the go-to bottoms for Southern Vietnamese men. Crafted from durable cotton, their wide legs provide comfort and flexibility for squatting, cycling, or resting. Designed to pair seamlessly with the Áo Bà Ba shirt, they form a functional, breezy outfit for hot climates. Whether in the rice paddies or relaxing at home, these pants reflect rural life’s humility, practicality, and resilience. image source

Áo Tấc Nam (Men’s Tac shirt:

Áo Tấc Nam (pronounced ow tuk nahm) is a formal five-paneled robe worn by Vietnamese men during imperial times, especially scholars and mandarins. Crafted from silk or brocade, it features wide, boxy sleeves and a straight, structured silhouette symbolizing order and dignity. The five-panel construction represents the five constants in Confucianism. Often richly embroidered with dragons or auspicious motifs, it’s paired with a khăn đóng turban and worn today during traditional weddings, ancestral rites, and cultural ceremonies. image source

Women’s attires:

Women’s Áo Dài:

The Áo Dài is Vietnam’s most iconic women’s outfit—a long, fitted tunic with high slits on both sides, worn over flowing trousers. Traditionally crafted in silk or lightweight cotton, it hugs the body with elegance, highlighting feminine grace. Brides wear it in ornate embroidery; students don it in pure white. The high collar and long sleeves add refinement, making it a national symbol of beauty, poise, and quiet strength.

Áo Bà Ba (Women’s):

A Southern staple, the women’s Áo Bà Ba is a collarless, button-down shirt paired with simple trousers. Made from soft cotton and often found in floral prints or pastel solids, it’s built for comfort in the Mekong Delta heat. Worn by rural women, it’s easy to move in—whether working fields or shopping in town. Equal parts practical and feminine, it reflects the everyday beauty of Vietnamese countryside life.

Áo Tứ Thân:

The Áo Tứ Thân, meaning “four-part dress,” is a traditional Northern Vietnamese garment with two front panels that tie over an inner bodice and two long back panels. Flowing and layered, it’s cinched at the waist with a contrasting sash. Made from earthy silks or cotton, it was once daily attire for women working in rice fields. Today, it shines in cultural performances and folk festivals, symbolizing heritage, humility, and grace.

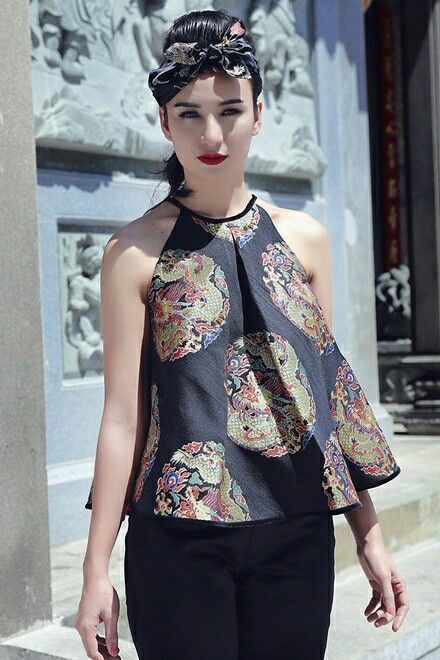

Áo Yếm-Inspired Tops:

The traditional Áo Yếm—a backless halter top once worn under robes—has been reimagined into trendy, standalone tops. Modern versions keep the triangular neckline but embrace bolder fabrics, cropped cuts, and street-style flair. Though originally an undergarment, the áo yếm now flirts with fashion-forward daring, often paired with jeans or skirts. A beautiful mix of nostalgia and rebellion, it captures Vietnamese femininity with a cheeky wink to the past.

Áo Giao Lĩnh

The Áo Giao Lĩnh is an ancient wrap-style robe with a V-shaped, cross-collar design. Once worn by nobles and scholars, its overlapping front panels tie gently at the side, creating a serene, symmetrical silhouette. Crafted in silk or linen, it flows gracefully with wide sleeves and a mid-thigh to knee length. Today, it reappears in cultural festivals and modern reinterpretations—softly structured, meditative, and deeply Confucian in its elegant simplicity.

Silk Palazzo Pants:

Silk palazzo pants—Quần Lụa Ống Rộng (pronounced kwun loo-ah ohng roong)—are a luxurious fusion of tradition and trend. Billowy and breezy, they drape like liquid, often in bold prints or soft neutrals. Rooted in classic Vietnamese wide-leg styles, they’re now a staple for fashion-forward women. Worn with cropped tops or formal tunics, they exude sophistication with every step—perfect for garden parties, gallery strolls, or breezy summer evenings.

Sườn Xám Cách Tân: A Modern Cross-Cultural Favorite

While the sườn xám—or cheongsam—originated in China, its modernized Vietnamese version, known as sườn xám cách tân (pronounced suhn zahm kak tun), has become a beloved fashion choice during Tết festivals, engagement shoots, and cultural performances in Vietnam. These updated dresses retain the high collar and side slits of the original but are reimagined with softer fabrics, youthful prints, shorter hemlines, and playful sleeves. Though not traditionally Vietnamese, their growing popularity reflects the country’s openness to cultural blending and its vibrant, evolving fashion identity.

Women’s Áo Tấc

Women’s Áo Tấc (pronounced ow tuk) is the female counterpart of the traditional ceremonial robe once worn in Vietnam’s imperial courts. It features a five-paneled structure, long straight form, and wide, rectangular sleeves, symbolizing formality and grace. Made from luxurious silk or brocade, it’s often adorned with intricate embroidery—lotuses, phoenixes, or floral vines. Worn with a khăn vấn (wrapped turban), the áo tấc graces royal reenactments, ancestral rituals, and traditional weddings, evoking noble elegance and historical pride.

Vietnam’s fashion accessories and footwear:

Nón Lá (Conical Hat):

(pronounced non lah and meaning “leaf hat” in Vietnamese language) Crafted from palm leaves stitched onto bamboo ribs, this hat shades farmers in rice paddies and dancers at festivals, its silk chin ties add a graceful touch. A timeless symbol of Vietnamese rural life.

Nón Quai Thao or Nón Ba Tầm ( Quai Thao hat)

Nón Quai Thao (pronounced non kwai thao), also called Nón Ba Tầm, is a wide, flat-brimmed hat traditionally worn by Northern Vietnamese women during festivals, folk dances, and Quan họ performances. Crafted from palm leaves over a bamboo frame, it’s larger and rounder than the typical nón lá. Decorative silk chin straps (quai thao) hang from the sides, adding elegance. Once associated with graceful courtesans and singers, today it symbolizes cultural pride, femininity, and the artistry of northern folk traditions.

Khan Dong (Traditional Turban):

A long, rectangular silk or cotton cloth—often embroidered—meticulously wrapped around the head, creating a structured turban. Worn by both men and women, it’s tied tightly to frame the face, with ends tucked or draped gracefully.

Khan Ran (Checkered Headscarf):

A floral-patterned cotton square, folded into a triangle and knotted under the chin. Rural women wear these while hauling baskets of fruit—sun protection with a folksy charm.

Vong Co (Necklace):

A choker-style necklace, often in gold or silver, with traditional motifs like lotuses or phoenixes. Commonly worn by brides with áo dài, it represents grace and cultural pride.

Guoc or guoc moc (Clogs):

(Pronounced gook / gook mok) Hollowed wood, polished to a gleam, with a strap across the toes. Click-clacking on tile floors, they’re the finishing touch to an áo dài, elevating the wearer (literally) with every step.

Trang Suc Bac (Silver Jewelry):

(pronounced chang sook bak)

Ethnic women wear bold silver earrings, cuffs, and necklaces. Beyond decoration, the jingling sound is believed to ward off spirits and celebrate identity through every shimmering piece.

Jewelry that wins visitors’ hearts.

Vietnamese Pearls:

Cultivated in coastal waters like Halong Bay, these pearls (often Akoya) glow with a silvery-gold hue unique to Vietnam’s mineral-rich seas. Strung into necklaces or stud earrings, they’re worn as heirlooms—brides drape them over áo dài collars, their luster echoing moonlight on water. Raw or polished, each orb carries the whisper of the ocean.

Lotus Pendants (Hoa Sen):

Delicate silver or gold lotus blossoms, petals unfurling in meticulous detail. Hung on chains or silk cords, they nestle near the heart—a symbol of purity rising from mud. Students wear them for exams; grandmothers clutch them during prayers, believing the flower’s resilience mirrors their own.

Dragon & Phoenix Rings:

Fiery dragons (masculine power) and phoenixes (feminine grace) coiled around gold bands. These aren’t subtle—think chunky, hand-chased designs worn at weddings. Couples slip them on as vows are exchanged, the mythic duo embodying harmony. Some elders say the dragon’s claws “grip luck,” while phoenix feathers “sweep in joy.”

Lacquerware Bangles:

Layers of resin-coated bamboo or wood, inlaid with crushed eggshell or mother-of-pearl. Bold crimson, black, or gold bands, their surface glossy as wet ink. Stacked on wrists, they click softly with movement—a wearable heirloom from craft villages like Ha Thai. Modern twists: geometric patterns or hidden messages etched beneath layers.